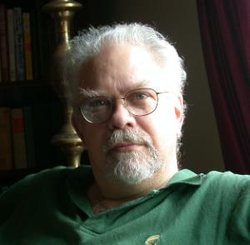

John Stoehr is the editor and publisher of The Editorial Board, a contributing writer for Washington Monthly and the former managing editor of The Washington Spectator. He was a lecturer in political science at Yale where he taught a course on the history of modern campaign reporting. He is a fellow at the Yale Journalism Initiative and at Yale’s Ezra Stiles College.

You can view John Stoehr’s articles syndicated by us here

Nonprofit and reader-supported, the Spectator reports from the ground on the excesses of the public and private sectors that distort our politics and undermine democracy. Each month in print and every day at

Nonprofit and reader-supported, the Spectator reports from the ground on the excesses of the public and private sectors that distort our politics and undermine democracy. Each month in print and every day at  Immanuel Wallerstein (1930-2019), Senior Research Scholar at Yale University, was the author of The Decline of American Power: The U.S. in a Chaotic World (New Press).

Immanuel Wallerstein (1930-2019), Senior Research Scholar at Yale University, was the author of The Decline of American Power: The U.S. in a Chaotic World (New Press). Rami George Khouri is an internationally syndicated political columnist and book author. He was the first director, and is now a senior fellow, at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut. He also serves as a nonresident senior fellow at the Kennedy School of Harvard University. He is editor at large, and former executive editor, of the Beirut-based Daily Star newspaper, and was awarded the Pax Christi International Peace Prize for 2006.

Rami George Khouri is an internationally syndicated political columnist and book author. He was the first director, and is now a senior fellow, at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut. He also serves as a nonresident senior fellow at the Kennedy School of Harvard University. He is editor at large, and former executive editor, of the Beirut-based Daily Star newspaper, and was awarded the Pax Christi International Peace Prize for 2006. From Europe to the Middle East, Asia, and North America, The Arab Weekly delivers the news and opinions that inform and shape decisions. We provide insight and commentary on national, international and regional events through the focus of the Arab world.

From Europe to the Middle East, Asia, and North America, The Arab Weekly delivers the news and opinions that inform and shape decisions. We provide insight and commentary on national, international and regional events through the focus of the Arab world. Richard Bulliet is Professor of Middle East History at Columbia University.

Richard Bulliet is Professor of Middle East History at Columbia University.